Fifteen Questions: Félix Blume about Animal Sounds and Interspecies Communication

Name: Félix Blume

Nationality: French

Occupation: Field recordist, sound artist, composer

Current release: Félix Blume is one of the artists contributing to harkening critters, an epochal, 33-track-encompassing compilation which “tunes in to the plethora of vocalizations, mechanical emanations, and any other acoustics phenomenon produced by animals.” The album is available from forms of minutiae

What sparked your interest in animal sounds? Are there any memories or experiences with these sounds that you can share?

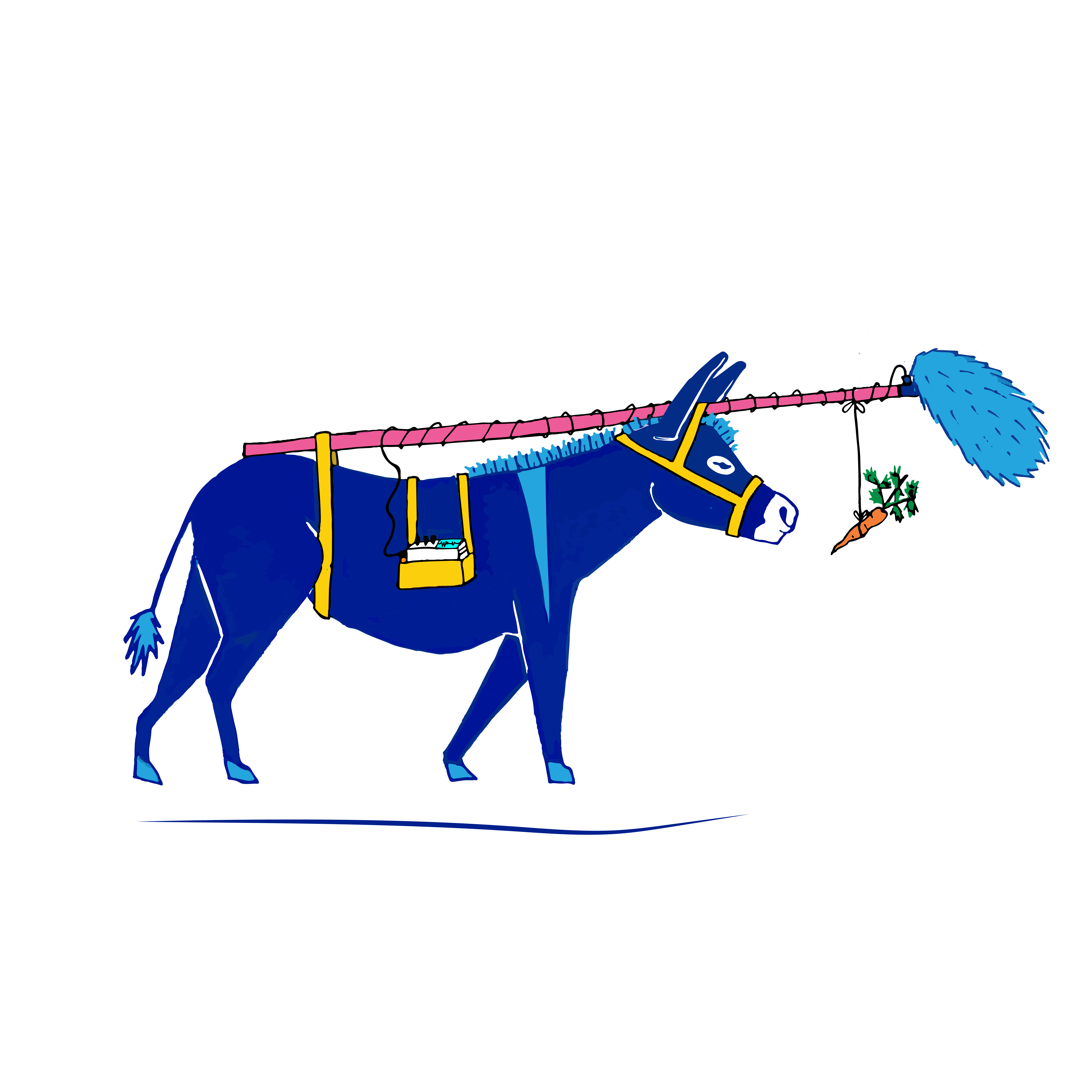

My interest in animal sounds stems from a broader fascination with everyday soundscapes and the act of attentive listening. Growing up in the countryside surrounded by domestic animals — a donkey, goats, chickens, a dog and cats — along with the presence of wild animals and birds, these sounds became an integral part of my daily life.

I had a close relationship with my donkey, Balthazar, whose braying varied greatly depending on the time of day or his mood. Each variation carried a distinct texture, rhythm, and emotion, which made me deeply aware of the expressive potential of animal sounds.

You can hear some of these sounds here:

What makes animal sounds interesting, inspiring, or just plain beautiful to you? Is there anything that continues to impress you about them?

I try to avoid creating boundaries between different types of sounds.

While some people prefer to categorize them — like Bernie Krause, who distinguishes geophony, biophony, and anthropophony for example — my approach is more intuitive and experiential. I focus on listening as a unified experience, embracing the interplay of sounds rather than isolating them. To me, the rustling of wind through trees, birdsong, and human voices in the background are not separate elements but part of a cohesive soundscape.

This perspective is what I aim to capture with my microphones: the richness of a shared sonic environment, where each sound contributes to a larger, immersive narrative.

Did or do you do any research on animal sounds? If so, what were some interesting findings?

Animal sounds are present in nearly all of my sound pieces and projects. What fascinates me most is the relationship between the sounds and the living beings — human or non-human — who produce them. I’m particularly interested in the dialogues, conscious or not, that emerge between different species and the territories they inhabit.

I find Steven Feld’s idea compelling: that humans create sounds influenced by the sonic environment around them. This concept applies equally well to animals, whose vocalizations are shaped by their surroundings.

Exploring these interactions reveals a deeper layer of connection between species and the landscapes they share, which I strive to capture and express in my work.

What did your first field recording set-up look like – and how has it changed over time?

In my early years as a student — first in France, then in Belgium — I didn’t yet have my own recording setup. This allowed me to experiment with a variety of equipment, including different recorders like DAT and Minidisc, and microphones such as shotgun and stereo setups.

The first recorder I bought was a Zoom H4, which allowed me to make some surprisingly decent recordings despite its simplicity. As my work as a sound engineer expanded, particularly for documentary film production, I invested in my own equipment. Over the years, I’ve used various Sound Devices mixer/recorders — from the 744T, 552 and 788 to the 633, 833, and MixPre-6 II. My microphone collection has also grown, primarily featuring Schoeps CCM microphones (in MS and ORTF configurations), alongside hydrophones, contact mics, and many others.

For a full list of my current gear, you can check it out here.

Do you have an archive of animal sounds? If so, what’s in it and how do you use it?

I don’t keep a separate archive dedicated solely to animal sounds, but I do maintain a comprehensive sound library of all my recordings. This library is organized with keywords, making it easy to search for animal sounds on my hard drive whenever I need them.

I also share some of these recordings on FreeSound where you can find sounds like donkeys, dogs, crickets or bees for example.

Have animal sounds been a direct inspiration on some of your other creative projects – if so, in which way?

Animal sounds — and the act of listening to animals — have directly inspired several of my creative projects.

One example is “Mutt Dogs,” a collaboration with Sara Lana. This project focuses not on the sounds animals produce, but on how animals listen. We placed binaural microphones (using Sanken Cos11D mics and a Zoom H1 recorder) on street dogs in the suburbs of Belo Horizonte, Brazil, capturing their unique auditory experiences to create a short sound piece.

My sound installation Swarm centers on the sounds of bees. Their buzzing was reproduced through 250 small speakers, creating an immersive sonic environment in the exhibition space.

These are just a few examples of projects where listening to animals and insects plays a central role in the creative process.

Tell me about your contribution to harkening critters, please. What were your considerations going in? When, where and how was it recorded?

I contributed 2 tracks to the album. One is the sounds of some frogs in the countryside of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

It was recorded in August 2019 in the small village of Serrinha of Alambari during the night, with an AB setup of 2 x B&K 4006 omni microphones on a SoundDevices MixPre6 recorder.

The other one is the recording of some buffalos in Oklahoma

It was recorded in May 2013 in the Tallgrass Prairie Reserve close to Pawhuska, Oklahoma (USA), with a MS setup Schoeps CCM41+CCM8 on a Sound Devices 788T recorder.

In both recordings, my goal was to immerse the listener in these natural environments, capturing the richness and detail of the animal sounds within their respective landscapes.

The press releases to harkening critters uses the word “signals” to classify the sounds on the CDs. Undeniably, there are many “musical” moments on harkening critters, but how do you feel about the using the term “music” for them? What sets “signals” apart from “music”?

Classifying sounds as ‘signals’ or ‘music’ is inherently complex, and the boundaries between them are often ambiguous. I believe the distinction depends more on the listener’s perception than on the nature of the sound — or signal — itself. This idea echoes the philosophy of John Cage, who encouraged us to experience all sounds from our surroundings as potential music.

In my own practice, I aim to blur these boundaries through listening exercises I conduct in workshops. These exercises invite participants to reconsider how they categorize sounds, encouraging a more open and fluid approach. You can explore some of these exercises here: Listening Exercises.

Do you think that true creative collaboration between animals and humans, as has been attempted for example by artists like David Rothenberg, is possible? Are there any such collaborations you’ve engaged in or would like to try?

I’m not sure how much we can talk about true creative collaboration with animals, since it’s unclear how aware they are of the recording process or our intentions. However, I don’t see this ambiguity as a limitation.

In my work, I often refer to animals or insects as collaborators, even if they didn’t actively choose to participate — at least not in the way humans do. That said, I always aim to approach these collaborations with respect for the animals and their environments. The fundamental difference when collaborating with humans is that they can make a conscious choice to participate or not, while animals don’t always have the same agency in that context.

Despite this, I believe that engaging with the natural world and its sounds allows for a meaningful dialogue — one that fosters a deeper connection and understanding between species.

Based on your thoughts, experiences, examples, or intuitions, do you think it is possible that examining animal signals will at some point lead to understanding and, eventually, communication? What is your personal threshold for considering interspecies communication as successful?

I believe that interspecies communication already exists — not just between humans and animals, but also between different non-human species. For instance, the second track on the Harkening Critters album by Mélia Roger and Grégoire Chauvot beautifully captures a dialogue between a fox and a group of common cranes (here).

[Read our Mélia Roger and Grégoire Chauvot interview]

Humans constantly communicate with domesticated animals. In my piece Horses Talk, I explored the ways humans give instructions to horses, which reflects a long-established form of communication. Similarly, shepherds communicate with their flocks, and people interact with their dogs in nuanced ways. These exchanges highlight the communication already taking place, though there’s always room for improvement.

I think we need to listen more attentively to non-human species to deepen these interactions. We must not forget that communication isn’t limited to sound — body language also plays a crucial role in interspecies dialogue. Successful communication, to me, involves recognizing these multiple layers and understanding the mutual responses and cues that arise from these interactions.

Some have argued that recording animals is a form of appropriation and that they should be compensated in some form. Do you have any thoughts on this?

It’s an interesting and important consideration. Respect for any being we encounter and record is essential.

The idea of compensation is complex, even when it involves humans. Determining what or how much to give for a recording that isn’t directly generating profit is challenging. At this point, I don’t think compensation for animals is something we can practically address, but perhaps the future will bring new insights or solutions.

Regarding appropriation, I prefer to see myself as a conduit between sounds and potential listeners — or perhaps even a pirate who shares sounds that don’t truly belong to me. This perspective is why I make many of my recordings available under a CC0 license on Freesound. I don’t feel like the author of these sounds.

When I record a bird singing in a tree or the wind rustling through leaves, who owns that sound? Is it the bird, the wind, the tree — or all of them? I don’t have definitive answers. Instead, I like to think that these sounds belong to everyone, inviting all to share in the experience of listening.