Reflections on sea, listening and sound installations: A conversation with Félix Blume

Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research

Volume 22 Number 2 www.intellectbooks.com 209

© 2024 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. https://doi.org/10.1386/tear_00132_1

Received 13 February 2024; Accepted 10 September 2024; Published Online January 2025

https://intellectdiscover.com/content/journals/10.1386/tear_00132_1

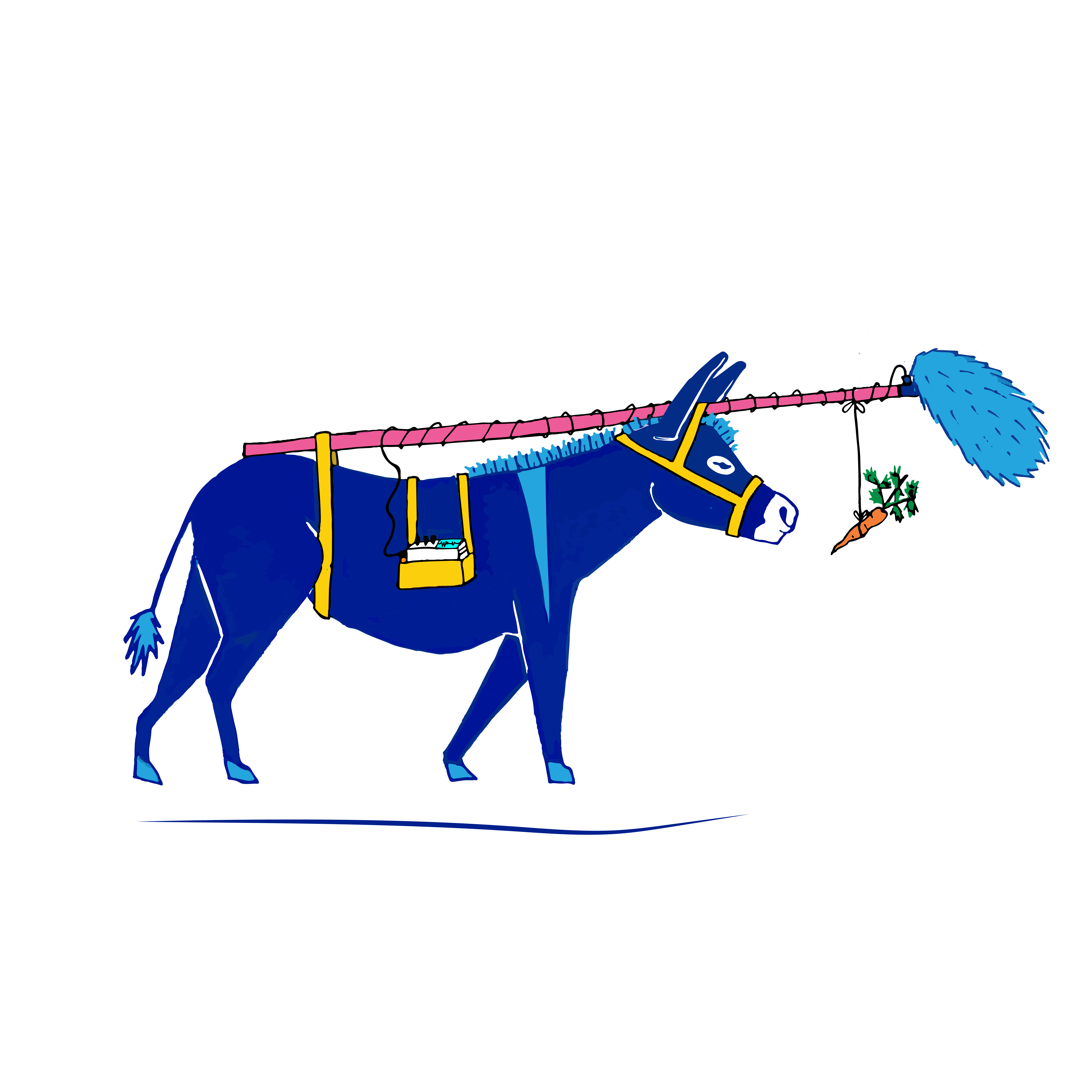

Figure 1. Félix Blume, Rumors from the Sea, site-specific sound installation. 2018.

FÉLIX BLUME

Independent Artist

BILL PSARRAS

University of the Peloponnese

The earth forms the body of an instrument, across which strings are

stretched and are tuned by a divine hand. We must try once again to

find the secret of that tuning.

(Schafer 1994: 6)

[S]ounds are as close to us as our thoughts.

(Berkeley, in Rée 1999: 175)

Bill Psarras (BP): One could describe conversation as a meeting of land and sea; as a shore that is constantly reshaped and that offers different vistas and aural points while walking across it. I think of our discussion as such: a dialogic movement across an imaginary shoreline of practices and ideas associated with two of your recent sea-oriented sound installations; Rumors from the Sea (2018) and Suspiros (2022). First, the sea and waves were employed in both artworks as a fluid and conceptual starting point for sonic interventions. The image of the sea is universal and such an environment reveals an archetypal soundscape, too. Waves and wind create an ambient sonic source; we keep returning to it as if ‘all roads lead back to water’ to echo Schafer (1994: 18). While vision has prevailed in landscape aesthetics across centuries, there are interdisciplinary voices that have argued for a ‘multisensory reconceptualization of place’ (Feld 2004: 182), which highlight the importance of sound, touch and other senses. Along with landscapes we also refer to soundscapes, which are defined as ‘the quality and type of sounds and their arrangements in space and time’ (Southworth 1969: 50). Schafer set the foundations for the development of soundscapes for decades; while recent voices describe them as ‘an acoustical composition that results from the voluntary or involuntary overlap of different sounds of physical or biological origin’ (Farina 2014: 3). Sound is a core element of our spatial experience, as we move, listen and interact with place – it has ‘an all-round auditory receptivity’ in contrast with vision which ‘sets a world as a series of objects in front of the eyes’ (Rodaway 1994: 94, 102). The ‘sound somehow eludes’, says Carlyle (2013: 15), and creates an auditory space without specific boundaries, ‘a space made by the thing not containing that thing’ (Carpenter and McLuhan 1960: 67). Such experience is apparent in both of your artworks, which is discussed in this article. It is interesting to see how sound has been a primal matter for your past practices. In some of your works, you balance sound art and sound engineering in a poetic way. Processes of listening and recording the human and the non-human – what is known as field recording – have often provided you with a sonic database. Yet, in a series of works, such as the Son Seul/Wildtrack (2012), one can identify an ongoing performative gesture. You do not mechanically record but perform the field recordings often through a bricolage of objects/microphones. It shows short sonic gestures (seen as video vignettes) that record encounters across different places, often resulting in poetic and absurd performances. In Schafer’s words ‘to record sounds is to put a frame around them’ (1973 in Drever 2002: 22), and Son Seul/Wildtrack reveals a series of filmic fragments. The latter show an art practice that although it is sound-oriented, blends sonic and visual layers in situ, and extends such a feature in sculptural objects (bamboos, ocarinas) in later sea installations.

Félix Blume (FB): For me, sound forms the foundational component and field of creation over the years – ‘as a modality of knowing and being in the world’ (Feld 2003: 226). My work was initiated as a dialogue between different practices: music and sound engineering that originates from film documentaries around the world. The process of travelling and recording sounds made me develop an interest in the relationship between sound and site. The mobile sound technologies informed not only how attentive I was to the sounds around me, but they also became performing objects often expanded in inventive ways (i.e. balloons, animals). In Son Seul/Wildtrack, these visual moments of sound recordings resemble what Tonkiss has suggested as ‘aural postcards’, indicating the capacity of sound to act as a souvenir of memory (2003: 303). Reflecting on the idea of a postcard entails a moment in time; it frames a landscape of experience in the logic of a mobile fragment. While it creates an oxymoron in terms of sound, as Droumeva says (2016: 76), such sonic gestures in my practice are framed excerpts of listening experiences across different contexts. The processes of recording, collecting and composing activated an interest in the act of sharing1 the sound. To some extent, I do not consider myself an owner of sound but as a performative mediator between sounds by humans or non-humans and later audiences. Sound, human and site can be a dynamic constellation, echoing Feld’s concept, which suggests that any inhabitant of a place produces a sound in relation to its sonic environment, which you can apply on the way tribes live in the middle of the forest, as well as different accents and languages, or, for example even the way street sellers announce their merchandise in Mexico City. My field recording practice through the years and its connection to cultural, environmental and anthropological aspects of sound, humans and environments – what others have described as ‘soundscape ecology’ (Pijanowski et al. 2011: 1213) – has been influenced by the perspectives of R. M. Schafer, Chris Watson, Francisco López, Hildegard Westerkamp, Jana Winderen, Luc Ferrari or Knud Viktor. In later exhibitions of such sound works, I had the feeling that space was an active element to experiment with, in various sculptural, visual or interactive ways; resulting in installations. I can identify a twofold methodological shift in my art practice: of spatial and material character. First, the implementation of such sound projects started taking place within public space or natural contexts, and second, while in nature, I began using other energies and materials to produce sounds; rather than electricity, speakers, microphones, players and recorders. Both signalled a turning point from the sound to the listening experience.

BP: This is an interesting shift to listening experience, which becomes a constantly changing environmental situation in your sea sound installations, Rumors from the Sea (2018) and Suspiros (2022), further discussed in this article. Listening experience takes place, able to unpack new worlds. Bull and Back speak on an ‘attuning of our ears to listening again to the multiple layers of meaning potentially embedded in the same sound’ (2003: 3), and it is this attuning process that becomes a significant reminder towards a sensory reconceptualization of the sea, its universal meanings and rhythmicities. Let us think of the sea waves performing themselves between an endless birth and collapse. They are geophonic events across centuries and cultures. Their sound is often described as susurration; making apparent ways that the sea whispers to us of its miraculous vastness. As mentioned earlier, the idea of soundscape has been expanded in contemporary scholarship, it is defined as a dynamic experience of the geo, the bio and the human elements (Pijanowski et al. 2011). In particular, three main elements compose a soundscape: the geophonic sounds, which stem from the environment, the weather and the Earth; the biophonic ones which are emitted by animals and the anthropophonic types that stem from human-oriented actions which often incorporate technologies, machines or other materials. While your aforementioned sonic gestures reveal a performative and exploratory approach, recent sound installations, Rumors from the Sea (2018) and Suspiros (2022) shift towards a collective listening experience, and to some extent an activation of a performative open score between sonic objects, the sea and visitors. Given the fact that both installations are activated and driven by the weather and the sea, one can consider repetition, rhythms and patterns as elements of an open score, one that converts environmental energies in an open-ended soundscape/intervention.

FB: Sea, weather and site are definitely an important part of both installations. Rumors from the Sea was a commissioned piece (four months), part of the Thailand Biennale. It was a site-specific sound responsive installation composed of hundreds of bamboos with an integrated flute at their top. Bamboo is a vital material of Thailand, with cultural and social practices deeply rooted in such South East Asian countries. A material that combines strength and elasticity, embedded in Thai culture with diverse symbolisms and eco-practices used as seawalls to slow coastal erosion. Selecting such a natural and culturally meaningful material was part of my gesture to develop attentiveness to place. These implanted, tuned objects were installed within water in a circular shape, having a floating pier as space for entering the sea level. The resulting piece was a bamboo-flutes orchestra activated by the waves; producing a unique non-stop concert 24 hours per day. The parameters of the sonic intervention depended on the tide, the direction, tempo and force of waves. The idea of the audience shifts from a fixed durational piece to an environmentally expanded listening experience of incoming and outgoing people at any time. Bodies standing, walking, lying down, sensing the sea and the air, ‘sharing viewpoints and earpoints’ (Myers 2010: 59) while listening to the momentary liveness of sounds encompassed by an atmospheric formation of sea-rooted objects.

Suspiros was realized in Zapotalito, Mexico, as both a sonic action and a sea-responsive sound installation made of clay ocarinas. In this work, participating children from the school of Zapotalito made their own clay ocarinas, and they went on sounding them as a call to the lagoon. In that location, a floating installation with a formation of handmade ocarinas sounded as the waves came through it; rendering the incoming water energy audible. Such dialogue between people with handheld ocarinas and water activated ones constituted an in situ performative framework, an invitation to listen to the place and the ecological problems it faces. In both projects, I conducted several workshops with local schools, in which the pupils were introduced to listening and drawing processes as well as to environmental issues. In both locations, sound installations were defined by tuned sonic objects made of site-oriented materials. In Thailand, the work was based on bamboo while in Mexico, clay was the primal matter for ocarinas. However, in both installations, the starting point was the sea wave energy, which had an interpreting rather than composing character. The method of tuning and incorporating flutes to organic materials provided them an interface, a possibility to produce sounds themselves in an improvised way. The latter draws to the idea of an open score, which was previously mentioned, with audiences able to experience each place and listen to such evolving soundscapes performed by natural elements. The contribution of local communities had a significant role in the production of these works. In both contexts, part of my practice was to provide them with an instrument to experiment and play with, followed by processes of placing bamboos in the sea or the tuning of the flutes.

BP: The capacity of both works to provide a framework of listening experience to people shows a way to become attentive to new interpretations of sea and natural energies. Both bamboo formations and floating ocarinas are transformed into sonic interfaces; where the meeting of different energies is translated to sound. Les Back argues that the importance of listening is ‘to admit the excluded, the “looked past”, to allow the “out of place” a sense of belonging’ (2007: 22). Both works highlight in aural and aesthetic ways the ubiquitous but invisible power of waves and tides, and, at the same time, the excluded yet emerging environmental issues of the sea. The idea of those crafted objects as instruments shows a performative and inventive framework; they act as units of improvisation by the sea and also as a transmission point of fleeting ‘sound events’ that people listen ‘as self-contained particles’ (Schafer 1994: 274), of the wider soundscape. The design and placement of such instruments made of natural materials echo in cultural and historical ways each particular place, the involved communities as well as the shoreline morphologies and sea as agents of performance. Bamboo trees have the capacity to bend with the wind and be elastic – and I also think of such material as a metaphor for emerging environmental issues such as sea rising levels and coastal erosion.

In Rumors from the Sea, one should probably listen to a wider soundscape consisting of the installation’s sounds, possible geophonic (i.e. waves, wind) and biophonic sounds (i.e. birds, animals), as well as anthropophonic ones (i.e. speech) upon the floating pier and across the shoreline. Your practice in Thailand and Mexico reveals an interesting line of processes: listening, floating, assembling, sculpting, participation or even transmission, which shape in direct or indirect ways your site gesture. To some extent, it renders you as a ‘producer of situations’ (Bishop 2012: 2) towards the formation of an in situ open score. Part of the implementation of such instruments was the process of tuning. I also think of it as a performative metaphor with poetic and environmental attentiveness towards a reconceptualization of sea, environment and communities. Various definitions of tuning exist, yet the ‘adjustment with respect to a particular frequency’ (Merriam-Webster 2024) delineates in a better way how such installations become physical interfaces of participatory attunement towards greater environmental frequencies and energies.

Figure 2. (a) (left) The process of tuning of the bamboo flutes in Thailand. 2018. (b) (right) Children from the Ban Klong Muang School with their drawings, Thailand. 2018.

FB: In both artworks, I used organic material from each place. It can be regarded as a gesture of placing a formation of objects in the sea, intending to allow natural elements to interact with them in playful and unexpected ways. The artworks have their own life through such natural flutes performed by the waves in the same way the aeolian harps with their strings were designed to be activated by the god of wind (Aiolos in Greek mythology). In my practice, the idea of a project sets the framework for experimentation with site, soundscapes and materials as well as for collaboration with local communities, often trying to understand their relations and their listening approach of the territories they inhabit. Unpacking the qualities of a place through its materialities, morphologies and stories was the foundation for the development of such ideas. Thus, experimentation with bamboo led me to extract inner separations, integrate a flute upside down on it and press it into a bucket full of water. That was a moment! Bamboo produced a sound, and methodologically speaking, it triggered a series of thoughts on the idea of a sea-responsive installation. Later stages of the work included a prototype presentation to the people of Biennale, meeting local builders specializing in bamboo as well as with the local village school as a playful way to integrate them in the creative process. During the following months, a technical collaboration with Bambugu team led to the construction and placement of the final bamboo sonic objects into the sea. An incoming wave entered the first rooted instruments and produced a series of sounds; indicating the success of the work in real conditions.

Reflecting on such collaboration in the field, it was the sharing of a listening experience, of a momentary sound, that constituted a common ground of communication and excitement for all of us, although we spoke different languages. The in situ composition of placing flutes in the sea and giving shape to the installation along with the bamboo builders was a participatory action which rendered them co-composers and the incoming waves as interpreters. The tuning of the flutes was done on a pentatonic scale; it was a participatory process with people and children of the village contributing to this. The tuning was implemented by cutting and adjusting the note of each flute on a pentatonic scale, from 37 cm for G4 to 20 cm for an A5. The idea of tuning the instruments that would be activated by the sea draws to the idea of the soundscape by Murray-Schafer, exploring a harmonized relationship between humans and nature. In my work, it was an attempt to create this kind of harmonization of that orchestra of bamboo flutes and waves. In a series of creative workshops with the schoolchildren, we explored ways of possible interpretations of the sound of the waves. Such depictions visualized a parallel wave of imagination towards personal entanglements of narratives, spirits and mythical creatures from the sea. During the creation process, each child learned how to build their own bamboo flutes; one for them, one for the installation. Such knowledge led to a kind of musical performance on the coast; a call to the sea in dialogue with the waves – a creative ritual moment. For local people involved in the implementation of Rumors from the Sea, the work constituted not only a site of listening experience but also an ephemeral site of collaboration and knowledge. The work Suspiros (Mexico, State of Oaxaca, 2022) had as a foundation of knowledge the Thailand piece. However, the new location and context shifted the idea to new paths. Suspiros was conceived as part of a residency at Casa Wabi. The place was associated with clay and that had a significant impact on my methodological approach. Some steps of the creation process included site visits and discussions with local people who had technical experience with clay.

Figure 3. (a) (left) Suspiros, sonic action and sea sound installation – audio-visual documentation, picture by Juan Pino. 2022. © Casa Wabi Foundation. (b) (right) Félix Blume, Rumors from the Sea, installation detail. 2018

Land artist Andy Goldsworthy has elsewhere mentioned the ‘binding of time in materials and places’ – ‘the work is the place’ he adds (1998: 6) – and such an idea echoes in both artworks where bamboo and clay are the primal matter. In Mexico, papaya trees were very common in the area, which I used as a base to shape the ocarinas in clay, and then the floating foundation was made of bamboo. Ocarinas are musical wind instruments, crafted objects across ancient cultures in Mexico and America. My approach and inspiration was a dialogue between clay and the lagoon’s morphology. My intention to connect the water and local people in sonic and participatory ways by setting the foundations for a listening experience included a collaboration with the local school of Zapotalito. The lagoon was facing an ecological problem due to tourism expansion and bad site maintenance which resulted in the loss of its connection to the sea. Through the interaction of waves with the floating formation of instruments, Suspiros suggested environmental attentiveness, reminding how ‘sound is about becoming aware of registers that are unfamiliar’ (Kanngieser 2015: 81). Boating towards the floating instruments, students created a performative sonic action by blowing into ocarinas they were holding, giving voice to the lagoon, a call coming from its waters towards people. The action was a video performance in the middle of waters; a gesture of dialogue between children and lagoon ocarinas; upon the waters.

BP: The particular qualities of each location are of great interest, given their ecotonal character. Ecotone is a transitional area between two systems, as in the case of intertidal zoning between sea and shoreline. Both installations did not take place in the open ocean, they were not based on drifting condition but intended to create sound points in those sites (shorelines, piers, lagoons). McCartney suggested the idea of sonic ‘ecotonality’ referring to emerging soundscapes of ‘more complex areas of the transitional and the in-between’ (Droumeva and Jordan 2019: 4). These physical boundaries exemplify a porous condition and creative edge, to echo Casey (2007), either speaking on shoreline or lagoon. In such geomorphological and environmental porosity, these installations seem to set the foundations for a liminal situation open to the weather and the waves. Your intention to create sonic interfaces where energies are interpreted to sounds provides a performative framework of new encounters for people; a liminal space of attunement to the invisible. It impacts their listening experience; they are part of a sensory atmosphere; encompassed by water, immersed in an evolving soundscape which they share with others upon the pier or boat. It is perhaps the conditions of boundary, transience and site-responsiveness which reverberate poetics and politics in Suspiros and Rumors from the Sea.

FB: I have always been interested in the idea of a porous threshold, as for example, between sea and land, night and day or human and non-human worlds. Both installations were defined by such in-between qualities. To be reminded of the term ecotonality, it is ‘the edge of the river, the edge of the forest, the edge of any discernible difference between one place and the next that produces a more interesting recording’ says the sound ecologist Gordon Hempton (2016: 80). I consider what he calls ‘edge-seeking strategy’ as a creative method to be attentive to the transitory. Moving from one context to the other marks a shift in location qualities. Yet, it is often challenging to categorize a place, a practice or a project. LaBelle suggests that ‘sound comes from the relations of the things’ (2010 in Kanngieser 2015: 81) and it is this friction between environmental energies and materials that reveals ‘paradigms and builds new formations’ (Kanngieser 2015: 81). I have often been attracted by such friction and boundaries, even in unconscious ways, yet it is a good remark. Sound has the power to give us freedom in the interpretation of it. Even when people listen to the same sound, their experience differs depending on cultural background, psychological mood, preoccupations and imagination.

There is no correct or incorrect listening, so it is the singularity of the listening act that interests such installations. As Westerkamp mentions, ‘listening cannot be forced […] it implies a preparedness to meet the unpredictable […] and as such, is inherently disruptive’ (2019: 46). In these cases, listening can provide people with a variety of interpretations of the installation; it invites them to an imaginative journey; to reflect on the relation of their bodies with the sea and environment. This draws to the experience of deep listening, as Oliveros describes it, one that ‘involves going below the surface of what is heard, expanding to the whole field of sound while finding focus’ (2022a: 5). Rumors from the Sea forms an invitation to the multiple sounds produced by bamboo-flutes orchestra but also those stemming from coast, sea and waves. The listening act is an active process, which, besides being contemplative or poetic, can be political, too. Let us think of listening as a way of understanding and attentiveness, of ‘admitting the excluded’ to rephrase Back (2007: 22). Oliveros adds that listening ‘is the way to connect with the acoustic environment, all that inhabits, it and all that there is’ (2022b: 5). Our natural landscapes are rapidly changing, and sea levels rise due to climate change. Coastal erosion has been a real problem in Thailand, as it is in many areas around the globe. Listening can become a political act, a gesture of attentiveness to wider rhythms and flows. One can listen to the Rumors from the Sea as a song, a dialogue and other times as a call, depending on the strength and direction of the waves.

We have undoubtedly become process-oriented but we still deal with objects.

(Ascott 2007: 189)

Figure 4: Félix Blume, Suspiros, installation detail. 2022.

BP: Both site-specific installations make apparent an ongoing and inventive methodological framework. This brings together different strands of the organic, the aural, the cultural, the social and the environmental. Such layers do not create a final object but platforms of experience, generated atmospheres activated by handmade units of sonification. To bring the inventive into discussion is to think of it as a creative oscillation between processes, objects and sea. A spatial formation of objects with capacity to tune the waves and the tide. We speak with words, but at the same time, in both of your works, language is waves itself. Lury and Wakeford describe inventiveness in creation as a way ‘to acknowledge and refract complex combinations of human and non-human agencies’ (2012: 4); methods that ‘enable the happening of the social world, its ongoingness, relationality, contingency, and sensuousness’ (2012: 2). The inventiveness in both works can be identified in the creative combinations of materials, humans and sounds that the sensory and social are enacted.

FB: Both projects focused on the idea of a sonic interpretation of sea energies, intending to create the conditions for an attunement with the environment. Tides and waves were a dynamic input: while strong ones entailed loud sounds, calm waters produced tiny rumours. To introduce a new sound in a place can change the natural balance of the local soundscape, thus it makes us question both this new sound and pre-existing ones, towards hybrid syntheses. That was part of the inventive approach; to acknowledge the sea and the natural as a source of sound, leaving electrical devices and speakers outside the conceptual and technical frame.

BP: Sound envelops us, it extends ‘across matter and beings’ indicating how ‘the world is rather with humans’ and not for them (Kanngieser 2015: 83). I feel that the sea speaks to us in so many ways. Rumours and whispers, vibrating etymologies of the ear.

References

Ascott, Roy (2007), ‘The cybernetic stance: My process and purpose’, Leonardo, 1:2, pp. 189–97, https://doi.org/10.1162/leon.2007.40.2.189. [Google Scholar]

Back, Les (2007), The Art of Listening, London: Berg. [Google Scholar]

Bishop, Claire (2012), Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, London: Verso. [Google Scholar]

Blume, Félix (2012), ‘Son Seul/Wildtrack’, Félix Blume, https://felixblume.com/sonseulwildtrack/. Accessed 10 September 2024.

Blume, Félix (2018), ‘Rumors from the Sea | Thailand Biennale | Félix Blume’, 28 October, Vimeo, https://vimeo.com/297546895. Accessed 10 September 2024.

Blume, Félix (2022), ‘Suspiros’, Vimeo, 6 April, https://vimeo.com/713732687. Accessed 10 September 2024.

Bull, Michael and Back, Les (2003), ‘Introduction: Into sound’, in M. Bull and L. Back (eds), The Auditory Culture Reader, Oxford: Berg, pp. 303–11. [Google Scholar]

Carlyle, Angus (2013), ‘Introduction: Listening perspectives’, in A. Carlyle and C. Lane (eds), On Listening, Axminster: Uniformbooks, pp. 15–16. [Google Scholar]

Carpenter, Edmund and McLuhan, Marshall (eds) (1960), Explorations in Communication, Boston, MA: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

Casey, Edward (2007), ‘Boundary, place and event in spatiality of history’, Rethinking History, 11:4, pp. 507–12, https://doi.org/10.1080/13642520701645552. [Google Scholar]

Drever, John Levack (2002), ‘Soundscape composition: The convergence of ethnography and acousmatic music’, Organised Sound, 7, pp. 21–22, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355771802001048. [Google Scholar]

Droumeva, Milena (2016), ‘Curating aural experience: A sonic ethnography of everyday media practices’, Interference, 5, pp. 72–88. [Google Scholar]

Droumeva, Milena and Jordan, Randolph (eds) (2019), Sound, Media, Ecology, London: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

Farina, Almo (2014), ‘Soundscape and landscape ecology’, in Soundscape Ecology, Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

Feld, Steven (2003), ‘A rainforest acoustemology’, in M. Bull and L. Back (eds), The Auditory Culture Reader, Oxford: Berg, pp. 223–39. [Google Scholar]

Feld, Steven (2004), ‘Places sensed, senses placed: Towards a sensuous epistemology of environments’, in D. Howes (ed.), Empire of the Senses, Oxford: Berg, pp. 179–92. [Google Scholar]

Goldsworthy, Andy (1998), Stone, New York: Harry N. Abrams. [Google Scholar]

Hempton, Gordon (2016), Earth Is a Solar Powered Jukebox, Port Townsend, WA: Quiet Planet. [Google Scholar]

Kanngieser, Anja (2015), ‘Geopolitics and the Anthropocene: Five propositions for sound’, GeoHumanities, 1:1, pp. 80–85, https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2015.1075360. [Google Scholar]

Lury, Celia and Wakeford, Nina (2012), Inventive Methods: The Happening of the Social, Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Myers, Misha (2010), ‘Walk with me, talk with me: The art of conversive wayfinding’, Visual Studies, 25:1, pp. 59–68, https://doi.org/10.1080/14725861003606894. [Google Scholar]

Oliveros, Pauline (2022a), ‘Pauline Oliveros on deep listening’, The Center for Deep Listening, https://www.deeplistening.rpi.edu/deep-listening/. Accessed 8 February 2024.

Oliveros, Pauline (2022b), Quantum Listening, London: Ignota. [Google Scholar]

Pijanowski, Bryan C., Farina, Almo, Gage, Stuart H., Dumyahn, Sarah L. and Krause, Bernie L. (2011), ‘What is soundscape ecology? An introduction and overview of an emerging new science’, Landscape Ecology, 26:9, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-011-9600-8. [Google Scholar]

Rée, Jonathan (1999), I See a Voice: A Philosophical History of Language, Deafness and the Senses, London: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

Rodaway, Paul (1994), Sensuous Geographies: Body, Sense, and Place, Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Schafer, Raymond Murray (1994), The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World, Rochester, VT: Destiny Books. [Google Scholar]

Southworth, Michael (1969), ‘The sonic environment of cities’, Environmental Behavior, 1:1, pp. 49–70, https://doi.org/10.1177/001391656900100104. [Google Scholar]

Tonkiss, Fran (2003), ‘Aural postcards’, in M. Bull and L. Back (eds), The Auditory Culture Reader, Oxford: Berg, pp. 303–11. [Google Scholar]

‘tuning’ (2024), Merriam-Webster Online, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/tune. Accessed 23 April 2024.

Westerkamp, Hildegard (2019), ‘The disrupting nature of listening: Today, yesterday, tomorrow’, in M. Droumeva and R. Jordan (eds), Sound, Media, Ecology, London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 45–65. [Google Scholar]

Suggested citation

Blume, Félix and Psarras, Bill (2024), ‘Reflections on sea, listening and sound installations: A conversation with Félix Blume’, Technoetic Arts: A Journal of Speculative Research, Special Issue: ‘Into/Across the Sea’, 22:2, pp. 209–20, https://doi.org/10.1386/tear_00132_1

NOTES

1 Part of practice was the sharing of recordings across online platforms (Freesound).

© 2024 Intellect Ltd